Dear Freddy,

The second day of movement against Fort Donelson (February 14, 1862), saw primarily action from the river and little on the land-front.

Commodore Andrew Foote, the antagonist at Fort Henry, you will recall, steamed up the Cumberland River with six vessels. The four ironclads and two wooden gunboats began bombarding the fort. Very little damage was done to Donelson, but the guns of the fort beat back the Yankee boats. Foote himself was wounded, his flagship and one other ironclad disabled, to the degree that they were unable to be steered. The other two were damaged as well.

Two cold armies sat and looked at each other--waiting.

In the Confederate headquarters, a council of war took place. It was decided that the very next day, the Confederates would evince a breakout--lead by Pillow--and head for Nashville. This break would be attempted at the southern end of the Federal line--their right, across from McClernand.

They began to set the stage for the dawn breakout...

Monday's letter shall contain the outcome. Do pay diligent heed to the preaching of the Word tomorrow, Fred.

Affectionately,

Grandfather

|

0 Comments

Dear Fred, All in all, it was not what I would call a momentous day, but still, the wheels of war continued to turn...and the Yankee's to invade. Charles grinned at his friend over the map's edge, "Freddy...I like it when your grandpa throws in some of that...wha'dhe call it? 'Literary fancy'?"

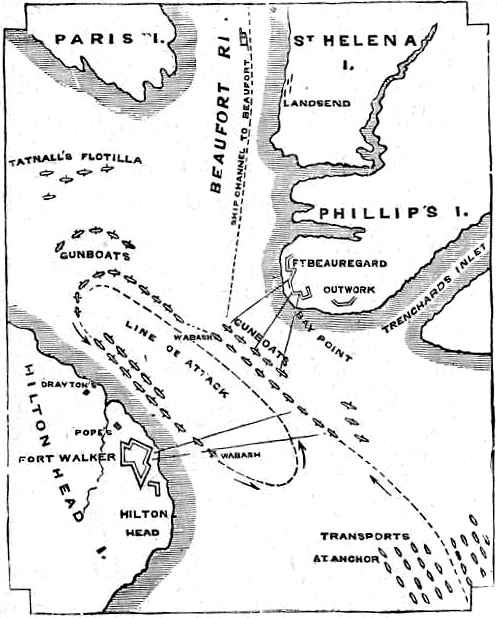

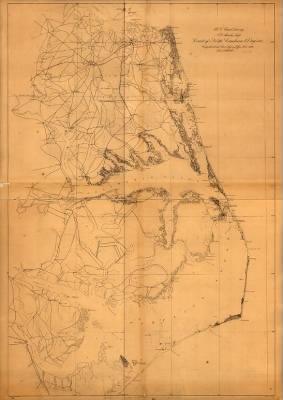

Fredrick reached for the map, "Let me see that now. Yes, he likes fancy phrases on occasion. I think he must have been in a good mood when he wrote that. Not that the subject is a happy one for him." Chuck shook his head, "No...I don't reckon it is. Still, I like it when he's funny." Their third room-mate pulled his head from his Latin book, "Huh. Chuck, you just like anything 'funny'. Now, will you guys be quiet? I'm trying to get my conjugations straight!" The two scholars of the late war observed each other with amused grins and then turned themselves to their own Latin books. Dearest Freddy, The boys scrabbled for the piece of paper and pored over it, their heads pressed together. Declaration of Paris; April 16, 1856. Chuck looked up, "What's a 'plen'...'pleni-potent-iary?" Fredrick gazed at the word intently, "I think...I think it must have something to do with government officials. Let's look it up to be sure." Practically before the words were out of his mouth, Charles Clark was racing down the hall to go borrow a dictionary from someone fortunate to actually own one. Moments later, he returned and the boys found their word. "You were right," Chuck remarked magnanimously. "A person, especially a diplomat, invested with the full power of independent action on behalf of their government, typically in a foreign country." They returned to James Hamilton's letter. Fifty-five nations ratified this treaty; the United States was not, initially one of them, though in 1861, they agreed to abide by it. As you may see from the document, the Union blockade of the Confederate coast line did not fulfill the standards. My Dearest Fred, James Hamilton scrounged around in a stack of old newspapers, intently scanning dates. At one point, he chuckled somewhat incredulously and murmured, "Bless her! I do believe my mother saved every newspaper she ever received." Finally, he found what he was looking for and taking it to his desk, he gently spread the old paper out, picked up his pen and began to consolidate the account for Fredrick. My Dearest Grandson,  Mr. Hamilton painstakingly traced a map he had found...and scratched in the Federal maneuvers. Satisfied, he returned to his writing. As you will be able to see, DuPont's plan consisted of an expanding elliptical line of attack--his gunboats raking the forts with each pass. *The majority of this post was drawn directly from Shelby Foote's The Civil War: A Narrative

|

IntroductionIf you are new to this page, you might like to read the introduction first. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed